André Salmon's "The Fable of the Tin Fish" explained and explored in the Met Museum's "Cubism and the Trompe l'Oeil Tradition"

Georges Braque, French, Argenteuil 1882–1963 Paris

Violin and Sheet Music: "Petit Oiseau." Paris, early 1913

Oil and charcoal on canvas 28 × 20 1/2 in. (71.1 × 52.1 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Promised Gift from the Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection

"Because of his family's background, the painter Georges Braque . . . belongs to that class of rich artisans and great entrepreneurs. His family painted, or had others paint for them, almost all the interior walls erected in Le Havre at the end of the last century. I am convinced that Georges Braque owes to this ancestry some of his most brilliant qualities.

One day he was discussing with Picasso the inimitable in painting, a favorite theme of modern artists. If one paints a gazette in the hands of a personage, should one take pains to reproduce the words PETIT JOURNAL or reduce the task to neatly gluing the gazette onto the canvas? They went on to praise the skillfulness of housepainters who extract so much precious marble and wood from imaginary quarries and forests.

Naturally, Georges Braque provided useful explanations, not sparing the juicy details of the craft.

He went on to say that a certain steel comb that helps housepainters achieve false marble and false wood can be run along a painted surface to achieve a simulation of veins and marbling.

We might smile at the seriousness brought to this type of discussion, because we might harbor the faintest prejudice and would not want to heed certain benefits that the artist finds, as he leans toward the beauties of the artisan's work. . . .

In short, Picasso and his guests agreed on the use of the housepainter's comb, but note that no one intended, however, to imitate these skillful artisans.

This is of extreme importance. An artist grows thinking about many things. He may even desire equipment that seduces him, but that's enough. He does not have to appropriate either the tool or the process. It is better to do what one of his own did (the painter [Louis] Marcoussis) - imitate the imitation."

--André Salmon, "The Fable of the Tin Fish," in Young French Sculpture (written in 1914 and published in 1919), translated into English by Beth S. Gersh-Nesic in André Salmon on French Modern Art (Cambridge University Press, 2005)

The Metropolitan Museum's groundbreaking exhibition Cubism and the Trompe l'Oeil Tradition, on view since October 20, 2022, will close on Sunday, January 22, 2023. It's a revelation, and it's beautiful! Moreover, no reproductions can equal the experience or the impact of this extraordinary curatorial effort that explains one of the least understood and most significant aspects of the Cubist movement, especially its collage. In essence, we learn that one of the oldest ways of judging artistic merit, the ability to copy nature to the degree that it fools the eye (in French, tromper - to deceive; l'oeil - the eye), played a significant role in the Cubist works by Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and Juan Gris. Since most of us look upon Cubism as the threshold to abstraction, the opposite of verisimilitude, the news that these Cubists assiduously studied and parodied trompe l'oeil may come as a shock. In the hands of the two brilliant art historians and curators Emily Braun, Distinguished Professor of Art History, CUNY Graduate Center and Hunter College, and Elizabeth Cowling, Professor Emerita, Edinburgh University, with the previous collaboration of the former curator of the Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Rebecca Rabinow, currently the director of The Menil Collection in Houston, Texas, we learn that Picasso, Braque and Gris (art dealer Daniel-Henri Kahnweiler's principal stable of artists) invented this peculiar visual language larded with visual jokes, puns, and codes to delight each other as it stoked their competitive natures.

Georges Braque, French, Argenteuil 1882–1963 Paris

Fruit Dish, Ace of Clubs, 1913

Oil, gouache, and charcoal on canvas

31 7/8 × 23 5/8 in. (81 × 60 cm)

Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris,

Gift of Paul Rosenberg, 1947

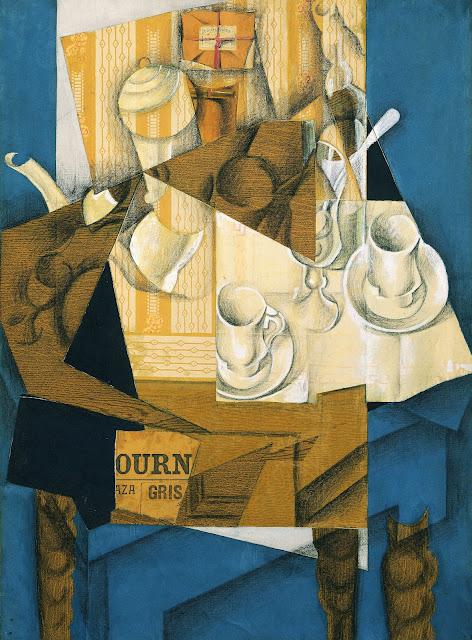

Juan Gris, Spanish, Madrid 1887–1927 Boulogne-sur-Seine

The Bottle of Banyuls 1914

Cut-and-pasted printed wallpapers, newspaper, wove papers, transparentized paper, printed packaging, oil, crayon, gouache, and graphite on newspaper mounted on canvas

21 5/8 × 18 1/8 in. (55 × 46 cm)

Hermann und Margrit Rupf-Stiftung, Kunstmuseum Bern (Ge 024)

From my perspective, we experience three overlapping exhibitions at once.

At the entrance to the exhibition, we review the legendary tale about the rivalry between 5th century BC artists Zeuxis and Parrhasius as told by the ancient Roman naturalist and philosopher Pliny the Elder in his Natural History (published in 77 AD). The story claims that Zeuxis and Parrhasius challenged each other to a painting duel, each trying to out fox the other with their skills of verisimilitude. Zeuxis unveiled his painting of grapes that were so faithfully rendered, birds flew down to peck at these counterfeits. Parrhasius then showed Zeuxis his handiwork, whereupon this renowned artist, born on the southern tip of today's Italy which was then part of Magna Grecia, attempted to pull back the "curtain" he believed covered his rival's work. He was mistaken. Thus, Zeuxis fooled the birds with his meticulous copy of nature, his trompe l'oeil (deceiving the eye), but Parrhasius fooled the artist Zeuxis by making him believe the depicted curtain was a real one.

Installation photograph by Beth S. Gersh-Nesic

What does this anecdote tell us? Early on in art history, the ability for an artist to copy nature faithfully, if not flawlessly, measured an artist's mettle for his contemporary audiences and his peers. It was the true proving-ground for an artist's self-worth. After this introductory text, we view and learn about the history of trompe l'oeil in fine and applied art, and its connection to still life, through various examples juxtaposed to Cubist works throughout the entire exhibition.

It's a fascinating story told briefly in the exhibition galleries and at length in Elizabeth Cowling's excellent essay in the catalogue (please buy the catalogue!). The exhibition "fleshes" out the written narrative. Trompe l'oeil had it heyday in the 17th and 18th centuries and then suffered from a decline in its critical reception toward the end of the 18th century (evident in Diderot's review of the Salon of 1763). It went downhill from there, well into the twentieth century, when it was associated with craft (housepainter's faux marble and wood) rather than art, an "intellectual" activity. The industrialization of trompe l'oeil on wallpaper seemed to seal the deal on that score. However, Picasso and Braque saw its value differently. Braque's decorative arts background and fine art painter's mind brought a new perception to trompe l'oeil techniques and execution, which in turn ignited Picasso's curiosity.

Juan Fernández, "El Labrador", Spanish, documented 1629–1657

Still Life with Four Bunches of Grapes, ca. 1636

Oil on canvas 17 11⁄16 × 24 in. (45 × 61 cm)

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid (P7904)

J. S. Bernard, probably French, active 1650s–1660s

Still Life with Violin, Ewer, and Bouquet of Flowers, 1657

Oil on canvas 32 x 39 1/2 in. (81.3 x 100.3 cm)

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of the Christian Humann Foundation (2008.55)

Cornelius Norbertus Gijsbrechts, Flemish, 1625/29–after 1677

The Attributes of the Painter, 1665

Oil on canvas 51 3/16 × 41 13/16 in. (130 × 106.2 cm)

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Valenciennes (P.46.1.111)

Edward Collier, Dutch, Breda ca. 1640?–after 1707 London or Leiden

A Trompe l’Oeil of Newspapers, Letters, and Writing Implements on a Wooden Board, 1699

Oil on canvas 23 1⁄8 × 18 3⁄16 in. (58.8 × 46.2 cm)

Tate. Purchased 1984 (T03853)

Wilhelm Robart, Dutch, active 18th century, Trompe l’Oeil 1770s

Ink, ink wash, watercolor, and chalk on paper 15 3/8 × 14 3/16 in. (39.1 × 36 cm)

RISD Museum, Providence, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Barnet Fain (2001.93.2)

Louis Léopold Boilly, French, La Bassée 1761–1845 Paris

Trompe l’Oeil ca. 1799-1804

Oil on marble with wood trim Diameter: 22 3/4 in. (58 cm)

Private collection, Canada

John Haberle, 1856–1933 Imitation 1887 Oil on canvas 10 × 14 in. (25.4 × 35.6 cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (1998.96.1

William Michael Harnett, 1848–1892, Still Life—Violin and Music 1888

Oil on canvas 40 x 30 in. (101.6 x 76.2 cm)

Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1963

The exhibition's history of Picasso, Braque and Gris' paintings and collages features their visual conversations with popular trompe l'oeil trends and subject matter, as well as among themselves. Thankfully installed in informative relation to each other, we readily see how well they spoke to each other through their inventive depictions and compositions. Together, they referenced and subverted conventional academic art practice and trompe l'oeil cliché as if commenting on the imposition of ubiquitous industrial decoration and trends in vogue during this new modern age. (I consider Cubism the original Pop Art.)

One particularly exciting gallery pairs Picasso's first collage Still Life with Chair Caning (1912), which incorporates a glued piece of manufactured oil cloth bearing a faux chair-caning print onto an oval canvas framed by a real rope, with his 1912 faux collage The Scallop Shell: Notre Avenir Est Dans L'Air. Still Life with Chair Caning belongs to the Musée Picasso in Paris, and The Scallop Shell belongs to the Met. What a treat to see these two contemporary works from different museums side by side! And, to add more sparkle to this exciting happenstance, we find their predecessor, Georges Braque's early Cubist painting Violin and Palette (1909), which belongs to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, right across the room from Picassos' landmark oval canvases.

In Violin and Palette, Braque seems to enlist trompe l'oeil for the nail inside the palette's hole and its shadow falling on the palette form. Art historians explain that the "realistic" nail and shadow at the top of the composition references the Cubists' departure from one-point perspective in the rest of the composition, drawing attention to the interplay between the two realities depicted in art. We can also glean a reference to the direction of the light falling on the objects arranged in this still life (a necessary ingredient for the artist bent on fooling the eye into imagining three dimensions on a two-dimensional surface).

Pablo Picasso, Spanish, Malaga 1881–1973 Mougins, France

Still Life with Chair Caning 1912 Oil and printed oilcloth on canvas edged with rope

11 7/16 × 14 9/16 in. (29 × 37 cm)

Musée National Picasso-Paris, Dation Pablo Picasso, 1979 (MP 36)

Georges Braque, French, Argenteuil 1882–1963 Paris

Violin and Palette, 1909

Oil on canvas 36 1/8 × 16 7/8 in. (91.8 × 42.9 cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (54.1412)

We also have Braque's first experiments with pasting faux wood wallpaper and painting faux wood on one canvas, hung next to each other on one wall: Fruit Dish and Glass, 1912 (Metropolitan Museum of Art) and Glass, Bottle, and Newspaper, 1912 (Metropolitan Museum of Art). These two works are accompanied by one earlier painting that includes stencil lettering (Homage à J.S. Bach, 1911-12) and a later painting that emulates faux wood wallpaper (The Guitar: “Statue d’Épouvante,” 1913). As a whole, this gallery supports the saga of Braque's discovery of faux wood wallpaper during the summer of 1912, when he and Picasso vacationed in Sorgues. After Picasso left Sorgues, Braque bought the faux wood wallpaper and began his first series of papier collés (glued papers), the first of this kind of collage in Cubism. That Braque chose to wait until Picasso was no longer around indicates their collaborations and mutual support did not suppress their ardent desire to outdo each other whenever the opportunity presented itself - Juan Gris included.

Installation photograph by Beth S. Gersh-Nesic

And what about Juan Gris? If nothing else, the sheer number and selection of Gris works could have been an exhibition on its own: an "Homage to Juan Gris." For here, alongside the better-known artists Picasso and Braque, the various iterations of Gris' collages and faux collages sing out with strength and fervor, not only due to their size but also their resplendent colors. I would suggest going through the exhibition a few times in order to savor Gris' exciting inventiveness and sensual applications of paint performed within a rigorous geometric composition.

Juan Gris, Spanish, Madrid 1887–1927 Boulogne-sur-Seine

Breakfast, 1914

Cut-and-pasted printed wallpaper, newspaper, transparentized paper, white laid paper, gouache, oil,

and wax crayon on canvas

31 7/8 × 23 1/2 in. (80.9 × 59.7 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (248.1948)

I also appreciated the organization of themes, such as this wall that demonstrates the relevance of Picasso's and Braque's frequent depiction of violins, a favorite subject among trompe l'oeil and still life painters. The curators also organized galleries that highlighted a single series by each artist, providing an opportunity to study in person several works of art that belong to different collections all over the world. Below are a few examples:

Violins in art

Picasso collages

Juan Gris and Picasso among Old Master still life paintings

Picasso's guitars

Also, while you are walking around the galleries, please pay attention to the exhibition designers' trompe l'oeil painted around the text panels. Such fun! Their humor caught me by surprise as I turned to re-read a text. And don't forget to look at the final text panel before you exit. I noticed that some people walk directly through the final door without looking back. Just in front of the exit you find Picasso's famous quote "art is a lie that makes us realize truth" accompanied by a playful trompe l'oeil flourish to send you out into the Met's magnificent hall of sculptures.

I have only one caveat, not a criticism. The history of Cubism exhibitions continues to inform and surprise. Professors Braun and Cowling heroically researched and developed a valuable method of analyzing Cubist paintings and collages. Their work benefits from all their previous publications and so many others who contributed to the realization of this show and other exhibitions on Cubism. Each contribution in turn has opened our eyes to new ways of understanding this radical movement, its artistic innovations and its commentaries on contemporary life. Therefore, we must bear in mind that there are many ways to analyze a Cubist work. Here, in this wonderful show, we acquire yet another one, but not the only one.

Please buy the exhibition catalogue Cubism and the Trompe l'Oeil Tradition (published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and distributed by Yale University Press). It includes excellent essays by the curators, art historian Claire Le Thomas, and Rachel Mustalish, conservator at the Met, as well as a valuable bibliography of sources that broaden our vision when it comes to the study of Cubism, its art and its artists. Fortunately, the images and evidence in this generous book will remain after the exhibition becomes a distant memory.

Pablo Picasso, Spanish, Malaga 1881–1973 Mougins, France

Fruit-Dish with Grapes, 1914

Cut-and-pasted printed wallpaper, laid and wove papers, gouache, and graphite on laid paper

18 7/8 × 16 3/4 in. (47.9 × 42.5 cm) Private collection

Pablo Picasso, Spanish, Malaga 1881–1973 Mougins, France

Dice, Packet of Cigarettes, and Visiting-Card, 1914

Cut-and-pasted laid and wove papers, charcoal, graphite, printed commercial label, and printed calling card on laid paper

5 1/2 × 8 1/4 in. (14 × 21 cm)

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Transfer from the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Collection, Yale Collection of American Literature (1980.130)

Needless to say, as we walk through the galleries, we must not lose sight of the sheer beauty the Old Master still life paintings and Cubist works bring to this landmark occasion. Yes, the first visit to this show may narrow your view, drawing you into the remarkable technical prowess of trompe l'oeil and the Cubists' fun playing with their specialized tools. A second visit might yield another meditation, perhaps on the shared subject matter or the distinct personalities each artist brought to their shared enterprise. And the third, well - the third should focus on the joy of looking, savoring and memorizing what these real objects accomplish that reproductions never can. Therein lies a precious "truth" which Picasso's refers to in the statement printed on the final wall of the show.

During this challenging period of navigating so-called facts and evident fabrications, an exhibition that studies the artists' preoccupation with truth in fakery comes at a timely moment for us all.

Pablo Picasso, Spanish, Malaga 1881–1973 Mougins, France

Still life with Compote and Glass, 1914-1915 Oil on canvas 25 × 31 in. (63.5 × 78.7 cm)

Columbus Museum of Art, Gift of Ferdinand Howald (1931.087)

Pablo Picasso, Spanish, Malaga 1881–1973 Mougins, France

Glass, Newspaper, and Die, 1914

Oil, painted tin, iron wire, and wood 6 7/8 × 5 5/16 × 1 3/16 in. (17.4 × 13.5 × 3 cm)

Musée National Picasso-Paris, Dation Pablo Picasso, 1979 (MP 45)

Comments

Post a Comment