Introducing Tarot Scholar Ronan Farrell's Translations of André Salmon's Cartomancie poems

Dear Readers,

It has been an absolute delight to correspond with the Tarot expert Ronan Farrell, best known for his blog: Traditional Tarot. Ronan Farrell and I met through an email exchange. Farrell contacted our wonderful colleague Jacqueline Gojard, University of Paris III (Sorbonne nouvelle). She forwarded his email to me. This introduction focused on a blog post about André Salmon, whose Tarot poems were published in Action, January 1921.

But before we get into all that, allow me to introduce the gifted and generous Mr. Farrell, who recently completed his Master’s degree in Buddhism in Taiwan. Below you will find a portion of our conversation published online at Bonjour Paris, November 26, 2021

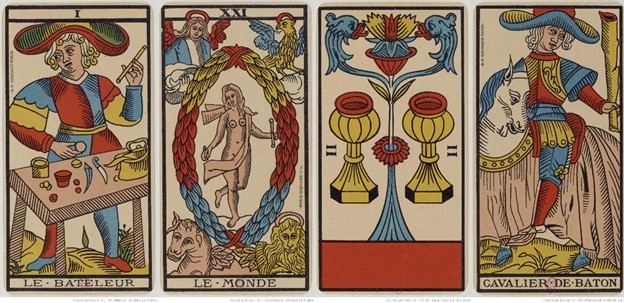

Grimaud Tarot de Marseille, c. 1930, courtesy of the BNF

Beth Gersh-Nesic: Hello, Ronan, welcome to Bonjour Paris. We are eager to hear about the history of Tarot cards and related subjects. But first, please tell us about you. Where are you from exactly? What got you started on this odyssey through Tarot history? And why?

Ronan Farrell: Hello Beth. To be honest, I was never very good at introducing myself, but here goes: I am from the west of Ireland, and am of French descent on my mother’s side, which explains my facility for that language.

“Odyssey” is, as we say in French, “un bien grand mot“! It strikes me that giving an answer in reverse chronological order might be more direct, so in a nutshell, the three-step answer to the question is as follows: Initially, I had set up a blog to use as a notepad to keep track of some texts and images I came across, as well as bits and pieces I’d translated for friends and correspondents, and I had left it on private mode for a few years until it struck me that I might publish some of these pieces and give readers an inkling of the variety and quality of the material written in French that remains more or less unknown in English. That was the proximate cause, I suppose.

Some years ago, I’d become intrigued by the entire phenomenon of Tarot – not only the images on the cards themselves, but their origins, real or imagined, and all of the varying and more or less inventive interpretations put forth by a host of authors over the course of the past few centuries. As a result, I began to read up on the subject, making notes, simply out of personal interest.

Of course, there is a bit more to it than that. When I was quite young, perhaps 10 or 12 years old, I remember seeing a pack of Tarot cards for the very first time in a small supermarket in a grimy north Paris neighborhood, where I was visiting a relative. It was at the check-out counter, next to the cigarettes, matches, batteries, chewing gum, all those last-minute impulse-buy items, and I clearly recall the impression that the gaudily-colored medieval-looking figures produced at the time. I managed to scrape together enough pocket money to buy a pack discreetly, and would look at the images, wondering what they were supposed to mean, and how they were supposed to tell the future. The accompanying booklet was not particularly useful in that regard for my 12-year-old self, perhaps something we will return to, and so I put them away in a drawer out of a sense of frustration at not being able to pierce their mystery. It must be said that at the time I knew absolutely nothing at all about the cards, nor even anything of the pop culture surrounding them. I’d grown up in a house without a television, but full of books, and it was simply something I’d no idea about, other than that it was a vaguely mysterious and typically French thing, as the name suggested: Tarot de Marseille. On holidays in France, I’d often seen people playing the game of Tarot, but they used the Tarot Nouveau deck, a pack of larger-sized playing cards with an extra suit of trumps depicting scenes of everyday 19th-century life, and certainly not nearly as intriguing as the crudely carved woodblock prints of the Marseille Tarot. So, the pack of cards lay in a drawer for years, and every now and then I’d take it out and look at it and ponder the meaning of it all, without understanding much more to it than that.

BGN: In your Salmon blog post you demonstrate the use of Tarots in poetry.

RF: Yes, that’s right. I had translated Salmon’s Cartomancy poems in the summer of 2020, but held off on publishing my translations for a few months as I wasn’t completely satisfied with the presentation. Eventually, I felt the new year was the perfect time to publish something rather different to what I’d done before and so put it out. But there’s always the question of broken links and new material appearing and so on, so I went back and checked and saw that Salmon’s works were still in copyright, which I hadn’t noticed the first time round. I then wrote to Jacqueline to mention my rendition of these poems, and she referred me to you. But I had found her email address on your Salmon website to begin with – so it was all very circular!

A. Camoin and Company, Marseille, c. 1890

BGN: Then we began to correspond about Salmon’s Tarot poems and his book Le Voyage au Pays des Voyants, which you read too. I re-read the book after we started to write to each other. And at that time, I had just discovered another website that translated Salmon’s Tarot poems. Do you know why Salmon wrote these poems? Your reference to the parlor games that required composing a poem about a Tarot card by drawing from the deck sounds like a possibility.

RF: To be honest, the background to Salmon’s poems is still a little obscure. My knowledge of the milieu, and of Salmon and his work in particular, is somewhat lacking, but my understanding of the Cartomancy poems is that they are the result of a number of different strands coming together: Salmon’s account of his visits to the fortune-tellers shows that he had a lasting interest in the divinatory phenomenon, and was well acquainted with its procedures, both from his investigations, but also from his friendship with Max Jacob whose interest in the conjectural sciences is well-known. Salmon does not appear to have been either a “believer” or a “practitioner” of these arts but comes across as more of an “informed but skeptical layman.”

BGN: That’s the journalist hat that Salmon wore to earn income.

RF: Some of the early Italian Tarot poems would have been accessible to Salmon as they are mentioned in the standard historical works available at the time in French, and it is possible that he read one of those for his research. In this type of game, a poem was spontaneously composed to describe a person or group of people, using the attributes of the Tarot cards. Interestingly, these parlor games using the cards became increasingly elaborate as the cards themselves became more widely available and developed into a sort of allusive theatrical performance played in aristocratic circles.

As to whether there is a more formal or even ludic aspect to the composition of the Cartomancy poems, I cannot say; as far as I know, Salmon’s memoirs are silent on the matter, but it is a tempting possibility. After all, the cryptic (or not-so-cryptic) cartomantic definitions provide a ready-made source of material for the poet; and these gnomic sentences, blended to the historic and cultural baggage of the playing cards – the kings, queens and jacks as historical or semi-legendary figures, with their own attributes and personalities – are so much symbolic fodder to be worked and reworked into a thematic set of poems.

André Perrocet (Lyons, late 15th-early 16th centuries), King of Clubs, c. 1491-1524

BGN: Now I wonder if Salmon’s poems started out as a casual studio challenge, like other games played among the members of Picasso’s Gang. Derain belonged to Picasso’s circle. Do you know if he brought the Tarot cards with him to do readings? Max Jacob, among Picasso’s closest friends, certainly did Tarot readings. Do you know anything about Max Jacob and his use of Tarot?

RF: Derain did read the cards for people he knew, as mentioned previously, and Apollinaire also talks about his arcane interests somewhere. I think that divination aside, Derain had a deeply philosophical understanding of occultism, and reading the cards was but one facet of this interest. Max Jacob has been studied in greater depth, and now there is Rosanna Warren’s new biography, which looks very promising. Jacob was mostly interested in astrology, and palmistry too, although I don’t think he wrote anything about the Tarot. He did write on astrology, not just poetry reflecting astrological symbolism, but also more involved efforts such as his Petite Astrologie or his contributions to the astrological treatises by Conrad Moricand, another member of that milieu. While the Surrealists’ use of so-called occult symbolism is now well-researched, the works of the previous generation of writers and artists would also be worth examining from this perspective as well.

BGN: Would you be willing to share your translation of Salmon’s Tarot poems and offer some insight into their meaning? Are they similar to the poems that come from 16th century Italy?

RF: Without being able to research the matter in greater depth, it is difficult to say whether these are poèmes à clef, or if they are simply using the court cards as a framework. Yet the poem entitled “Encounters” is quite revealing, since the very title reflects a cartomantic concern – the combined meaning produced by two cards drawn in conjunction. This view is further justified when we look at the text: It reads as a pastiche of the sort of sentences found in manuals of cartomancy, and in fact, most of the sentences contain keywords taken from the cartomantic tradition which ultimately originates with Etteilla in the late 18th century.

To my mind, the unanswered question here would be to know whether Salmon prefigured the formal experiments of the Oulipo group (Raymond Queneau, Italo Calvino, Georges Perec, Jacques Roubaud etc.) by drawing cards and attempting to write a poem around the combinations of meanings, or whether he simply picked and chose some of the keywords from a cartomantic manual. I think it would further our understanding of the creative relation between games, symbols, and the structure of literature.

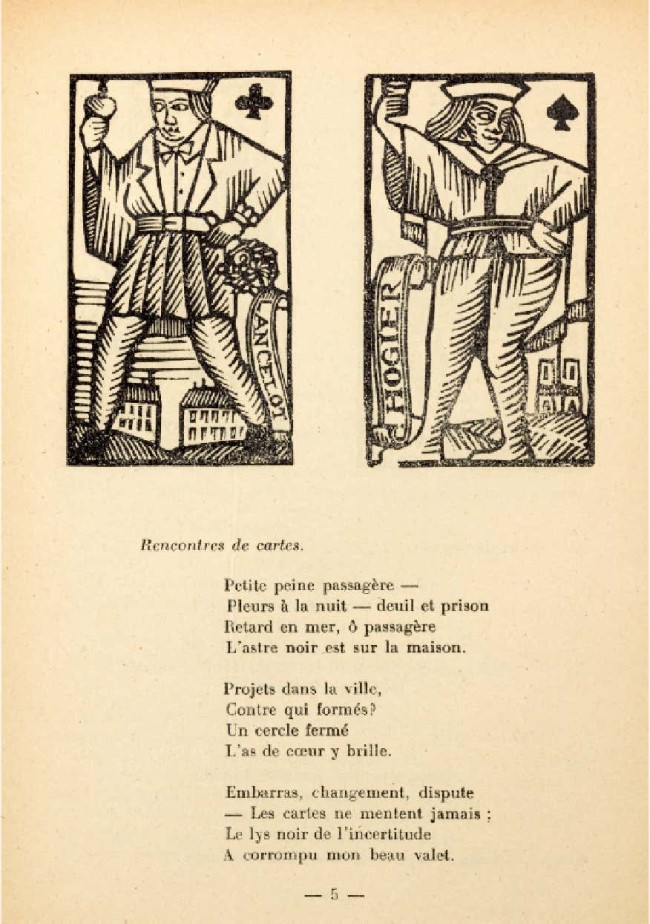

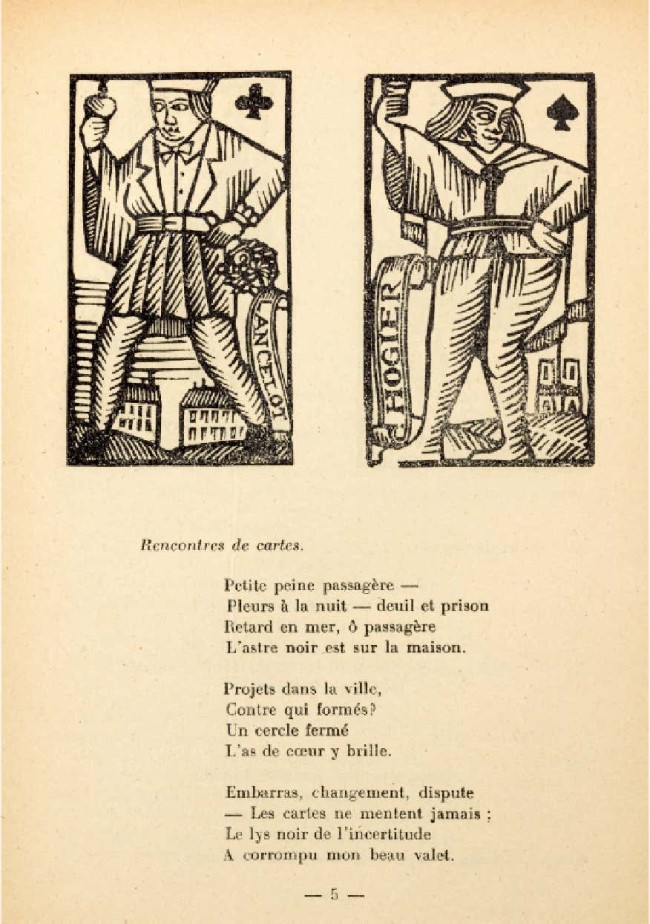

André Salmon, “Rencontre des cartes,” Cartomancie, published in Action, January 1, 1921. Illustrations : Apa (Felíu Elías Bracons)

Encounters

Trifling temporary troubles —

Tears in the night — bereavement and prison

Delays at sea, O passenger

The dark star is above the house.

Plots in the town,

Formed against whom?

A closed circle

Wherein the Ace of Hearts shines.

Bothers, changes, disputes

— The cards never lie;

The black lily of uncertainty

Has corrupted my handsome valet.

BGN: Wow, Ronan! You really nailed this translation. A tough nut to crack, too. I tried to translate it while we compared other versions of Salmon’s “Cartomancie.” You successfully captured its essence and kept the meter. A difficult combination.

The figures featured above these verses are Lancelot (lover of King Arthur’s wife Guinevere) and Hogier (Ogier, the Dane, one of the Twelve Legendary Knights of Charlemagne). A Valet in Tarot became the Jack in playing cards.

These cards and the Marseille deck probably inspired the artist Apa (Felíu Elías Bracons) who illustrated Salmon’s poems.

Thank you so much, Ronan, for your generous and highly informative responses to my questions. Are you going to publish your history of Tarot cards within the near future?

RF: You are very welcome. Right now, I have a number of books in various stages of completion. First off, I have an edition of Eudes Picard’s seminal Tarot manual ready to be published, another classic of the Tarot literature, and an anthology of late 19th century-early 20th century material, all of which I intend to publish myself. Then, I have a translation of Artaud’s New Revelations of Being in the works, and finally, I have been making notes towards a sort of literary history of the Tarot, which I suppose has been my main focus these past few years. That will take some time yet as I keep discovering new material. In the meantime, readers can subscribe to my blog to receive news of updates and publications, and I am open to offers from enterprising publishers as well!

BGN: Best wishes to you, Ronan, for all these exciting projects and endeavors. I look forward to seeing your Tarot studies in book form. In the meantime, your blog is a feast for the eyes and mind.

For Further Reading and Discovery

Ronan Farrell’s Blog: Traditional Tarot: Desultory Notes on the Tarot https://traditionaltarot.wordpress.com/

Ronan’s post on André Salmon’s Cartomancy: https://traditionaltarot.wordpress.com/2021/01/15/andre-salmon-cartomancy-excerpts/

Le Musée Française de la carte à jouer: https://www.museecarteajouer.com/

Comments

Post a Comment